U.S. Coach Is at Home in Moscow : But After a Week, Alla Svirsky Leaves With Fewer Regrets

- Share via

MOSCOW — Alla Svirsky left for home in the rain Friday.

She had been in Moscow for one week, long enough to realize that the Soviet Union has nothing to offer her except a few close friends and relatives and a few memories, some more pleasant than might be expected.

Before she arrived at Sheremetyevo Airport on a flight from New York last Saturday, she thought she would feel differently about Moscow, more attached somehow.

She hadn’t wanted to leave the Soviet Union in 1974 to live in Los Angeles, but her husband was adamant about it. Finally, reluctantly, she decided to go with him.

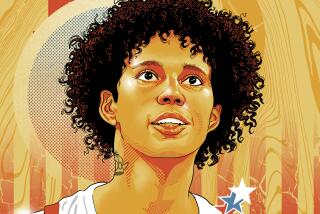

Svirsky told her story as she stood outside the lobby of her hotel, the Rossiya, next to Red Square and the Kremlin, and waited for a bus that was to carry her and the U.S. rhythmic gymnastics team to a workout at the Olympic Sports Complex. She is the team’s coach for the Goodwill Games.

“We’re being watched, you know,” she said, glancing subtly over her shoulder toward two people who weren’t trying to hide their interest in her. They were plainclothes security officers.

“Every step I’ve taken, they’ve followed me,” she said, her voice still heavily accented. “I don’t care.”

She said she was more concerned about how her gymnasts would perform that night, Wednesday, in the all-around competition against five other teams, four of them ranking among the world’s best. The competition she said, was better than it was at the Olympics. She said she hoped one or two of her gymnasts would score high enough to advance to the individual finals the next night. None of them did.

Three of the gymnasts selected for the U.S. team also came to Los Angeles from the Soviet Union, although the parents of Shura Feldman, 15, would not allow her to go to Moscow. The others, Marina Kunyavsky, 21, and Irina Rubinshtein, 16, were here. All three train at Svirsky’s Los Angeles School of Gymnastics in Culver City. The school’s pianist, Bella Frank, is another Soviet immigrant who was allowed to return for this competition.

Svirsky said she did not think the gymnasts were having much fun in Moscow.

“They are spoiled,” she said. “They miss the things they have back home, their food, their diet drinks, their stores. We have so much.”

During one workout early this week, Svirsky was reacquainted with several coaches she had known when she was the gymnastics coach of a club in Odessa, in the Ukraine. She said they were cool toward her.

“Everybody resents me,” she said. “I’m a bad example for them because I’m successful. The propaganda here is that you will starve if you go to America. They know that I have a good gymnastics program, that I am happy and that I love America.”

If it is an issue of dollars and cents, or rubles and kopecks, Svirsky and her husband were also successful in the Soviet Union. She said they would have been classified as upper middle class if the Soviet Union had a class system, which, of course, it does not.

Svirsky said she had been content. Her husband had not. He sought an invitation from an uncle who lived in the United States. The uncle died six months after they arrived in Los Angeles.

“I was happy (in the Soviet Union) because I didn’t want to see anything,” she said. “I had 22 little gymnasts in Odessa who were like children to me. I was comfortable here. Everybody knew me. We had a good car and a good apartment.

“We were let out of the country because we were Jews, but that’s not the reason he wanted to leave. He felt limited in life. Here, there are walls. He wanted to go where there was more opportunity.

“We had silver and furniture and money. He said, ‘Leave it. I don’t want it. Let’s go.’ I was so confused. But now I see that he was absolutely right.”

Her husband was a builder in the Soviet Union. In his first five years in Los Angeles, he was a welder. But he eventually saved enough money to start his own business as a contractor and is now building a house for his wife and himself in Hollywood Hills.

It will have 5,000 square feet, somewhat more expansive than what the Soviet government allows, still following Lenin’s guidelines.

Alla Svirsky’s life is good. She was wearing a pullover blouse that had the name of its Japanese designer on the front. She said she bought it on Rodeo Drive.

“My husband has worked hard,” she said. “But in the United States, if you work hard, you can get very big results. Here, there is no certainty.”

On a tour this week of Moscow, where she was born and reared before moving to Odessa, Svirsky was taken to an opulent international hotel, known here as the Home of Hammer. It was built by American industrialist Armand Hammer, who was the most popular capitalist here until Ted Turner brought his Goodwill Games to town.

She was introduced to a Soviet diplomat, who asked: “Why did you leave here?”

“Lines,” Svirsky said. “I hated the lines.”

Because of shortages of consumer goods, there are lines outside most of the stores throughout the Soviet Union. People will get in lines even if they don’t know what’s being sold just so they won’t miss anything good, such as shoes or toilet paper.

“He (the diplomat) told me, ‘We can’t do everything. We had war. You didn’t have war in your country,’ ” she said. “I told him, ‘That was 40 years ago. That’s no excuse.’

“He then said that he makes 150 or 200 rubles ($211 or $281) a month and still has caviar. But then he told me that he sells it to the tourists. So he is a capitalist. Taxi drivers take you for a ride that costs two rubles and then say they want five rubles. You have to be a capitalist here to make up for the deficits.”

One improvement she has noticed in Moscow in the last 12 years is that there are fewer drunks on the streets.

“You can’t get much production from a drunk person,” she said.

Arriving at the same conclusion, Soviet leader Mikhail S. Gorbachev has closed many liquor stores and limited the hours that other stores may remain open. In the past, wine could be purchased from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. and vodka from 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. Now, all alcoholic beverages may be sold in the liquor stores only from 2 p.m. to 7 p.m.

As a result, there always are long lines outside the liquor stores, often equaling in length the lines of people who wait to see Lenin in his Red Square mausoleum.

The first thing Svirsky did upon returning to Moscow was visit the house where she was born. She took a picture.

“It made me feel a little bit touchy,” she said, meaning that it touched her.

Otherwise, she said, she has felt little sentiment for Moscow.

“I hate to say it because people will think I don’t feel anything,” she said. “But I never miss anything, just my friends and relatives.

“Maybe I’m terrible, but I’m very comfortable over there.”

The only person from her past who has visited Svirsky is her former assistant coach at the club in Odessa. She now lives in Moscow.

Before Svirsky left Moscow, she said she was going to give all the clothes she brought to her friend.

“Shoes, handbags, everything,” she said.

She said she knows it probably is the last time she will see her friend. She called an aunt in Moscow the other day and discovered that her uncle died two years ago. The aunt was cordial but did not invite her to visit. Svirsky said she understood.

“My husband, I think, was worried that I would be very sentimental and that I would not want to come home again to Los Angeles,” she said. “But now I recognize more than ever that my home is there.”

Two U.S. boxers win in the Goodwill Games. Story, Page 13.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.