Despite Predictions of Tests in 1987, Safe AIDS Vaccine Is Years Away

- Share via

At a recent World Health Organization conference in Geneva, researchers predicted that the first human tests of experimental AIDS vaccines will begin sometime in 1987. But it will take years to develop a safe and effective vaccine against the deadly disease--a prerequisite to the marketing of any such immunization.

And nearly overlooked in the international race to begin testing an AIDS vaccine are key social and ethical questions, such as who will be asked to volunteer for the potentially risky experiments and how these trials should be coordinated.

“Under the best of circumstances, large trials to determine whether an AIDS vaccine works are several years away,” said Dr. Jonathan Mann, director of the World Health Organization’s AIDS program. “But we might be able to significantly accelerate vaccine development if we start planning now for these trials. This is not a minor point.”

In the United States, approval by the Food and Drug Administration is necessary before human tests of experimental vaccines can begin. And before such approval is sought, most researchers believe that the protective effects of experimental vaccines should first be confirmed in chimpanzees, the only species other than humans that can be infected with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome virus.

So far, no such successful tests have been reported in the medical literature. But many research groups, including those at Genentech in South San Francisco, Oncogen in Seattle and the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md., have completed lab experiments and tests in other animals of their vaccine preparations. Some of these groups are already conducting chimpanzee tests.

Compared with the time it has taken to develop other widely used immunizations, the pace of AIDS vaccine research is swift.

The discovery of the AIDS virus was announced less than three years ago. In contrast, 18 years elapsed between the discovery of the deadly hepatitis B virus in 1964 and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s final approval of a vaccine in 1982, according to Dr. Baruch Blumberg of the University of Pennsylvania Medical School, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1976 for discovering the virus.

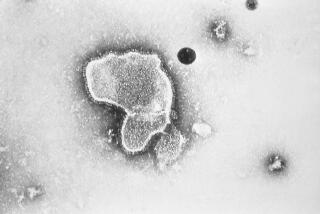

The AIDS virus attacks the body’s immune system, leaving the infected individual vulnerable to a variety of infections and tumors. Like the hepatitis B virus, it is transmitted by intimate sexual contact, through the blood and from an infected mother to her newborn. As of last week, 28,905 Americans had been diagnosed with AIDS and 16,229 had died.

Vaccines, which contain weakened or dead germs, work by inducing the body’s immune system to produce protective molecules called antibodies. Vaccines are given either by mouth or by injection into the muscle or under the skin.

Vaccines are designed to protect healthy people at risk of acquiring a disease. They are much different than treatments, which are meant for people who have already acquired a disease.

Indeed, a successful AIDS vaccine might not even be recommended for many people, including those at low risk of becoming infected with the virus because they are not sexually active or because they are involved in monogamous sexual relationships. Even vaccinated individuals will likely still be advised to avoid high-risk behaviors for acquiring the virus, such as intravenous drug use and sexual intercourse with multiple partners.

Before human tests of an AIDS vaccine can begin, key scientific obstacles must be surmounted.

There is skepticism, expressed at an AIDS vaccine meeting in Paris in October, about the effectiveness of the most common experimental approach--to make a vaccine from the whole or part of the envelope protein of the AIDS virus.

There is concern that antibodies against the envelope protein, which are also made by patients infected with the AIDS virus, will be inadequate to protect against infection.

There are also many strains of the AIDS virus; vaccination against one strain may not prevent infection with others. An AIDS vaccine, like the polio and flu vaccines, may need to be made from multiple virus strains.

There are no animal models for successful vaccines against the “type C retroviruses,” the family to which the AIDS virus belongs, although there has been success against other types of retroviruses, notably a virus that causes an AIDS-like disease in monkeys. There are no vaccines at all against retroviruses that infect humans.

Complicating vaccine research further is a shortage of chimpanzees. There are only 1,600 chimpanzees in the United States, of which more than 300 are being considered for AIDS research, according to a report in Science magazine in September.

Researchers are also very concerned about safety issues, even more so than for other experimental immunizations. This is because the AIDS virus attacks the body’s immune system, the same system that an immunization is designed to strengthen.

Volunteers for all vaccine tests will be screened with blood tests to make sure that they are not already infected with the AIDS virus, according to Dr. Dani Bolognesi of the Duke University Medical Center, a vaccine researcher.

The first human tests will focus more on safety considerations than the possible protective effects of a vaccine. In these “Phase I” trials, a small number of people, perhaps 10 to 30, will be injected with an experimental vaccine and then closely monitored through blood tests and exams for possible side effects, including immune system damage or even the development of AIDS.

Those asked to volunteer will likely be healthy individuals at “absolutely zero risk” of acquiring the disease, according to Robert Gerety, director of the virus and cell biology department at Merck Sharp and Dohme in West Point, Pa, which developed the hepatitis B vaccine and recently started an AIDS vaccine program.

‘Just Another Step’

Drug companies often feel so positive about their new vaccines that they ask for volunteers from among their own employees, Gerety said. “People should not be confused that (a Phase I trial) means that we have a vaccine,” he said. “It is just another step in the experimentation.”

In the second phase of human tests of AIDS vaccine, researchers will try different dosage schedules to see which produce an adequate level of immune response, according to Mann of the World Health Organization. A substantially larger number of volunteers will be necessary.

Potential volunteers for the second phase of trials would include those who had not already been exposed to the virus but might benefit from any protective effects of the vaccine, such as medical students in the United States or adolescents in Africa who are not yet sexually active, according to Gerety.

The most “complex and difficult” questions will arise when full-scale vaccine trials begin, according to Mann. These are likely to involve comparison of an AIDS vaccine to a placebo in individuals at moderate to high risk of developing AIDS virus infections, such as the spouses of hemophiliacs, male homosexuals in the United States, or sexually active teen-agers or adults in Africa. But it may be unethical to allow trial participants to continue to engage in high-risk activities when health education could lessen their likelihood of AIDS virus infection.

Such trials will need to be conducted simultaneously in multiple areas of the world, Mann said. Because of the long incubation period of AIDS virus infections, patients will need to be followed for at least several years, which may pose practical problems in some Third World countries or for trials involving intravenous drug users.

In the United States, liability concerns will also be a factor, perhaps even more so because of the widespread fear of the disease. A new law in California addresses this issue by limiting manufacturer’s liability for AIDS vaccines, establishing a state claims fund to pay for vaccine-related injuries and providing $6 million to subsidize clinical trials of an FDA-approved vaccine.

Public health officials, such as Mann, also believe that open scientific collaboration is an essential part of human vaccine trials.

Open discussions would avoid uncertainty about the scientific validity of the results and assure that the tests are conducted in accordance with ethical principles. Indeed, in January the World Health Organization plans to establish an international advisory group to coordinate this process.

But recent reports of secret tests by French scientists in Zaire of a form of immune system therapy for people infected with the AIDS virus already has raised questions about the willingness of researchers to cooperate and share information.

The leader of the research team, Dr. Daniel Zagury of the Pierre and Marie Curie University in Paris, said in a recent telephone interview that he was “under oath” to the Zaire government not to discuss the experiments.

If a successful AIDS vaccine is developed, public health officials will still have to decide who should be immunized. The recommendations for vaccination against hepatitis B, which is transmitted in the same ways as the AIDS virus, may provide some clues.

In the United States, the list includes health care workers, male homosexuals, intravenous drug users, and household and sexual contacts of hepatitis B carriers. For the Third World, an international group of medical experts recently recommended that all infants be immunized.