Gene Therapy OKd for Cystic Fibrosis Patients : Health: Federal panel’s approval of experiments will be technique’s first test against a widespread disease.

- Share via

WASHINGTON — A scientific panel Thursday gave its approval for experimental gene-therapy treatments of cystic fibrosis patients, marking the first time the revolutionary but still-developing technique will be tried against so prevalent and lethal a disease.

The unanimous approval by the federal Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee underscores the accelerating pace of gene-therapy experiments. Until now, they had been tried only against a handful of extremely rare genetic diseases and a few types of cancers for which there are no cures.

“This is a major watershed event,” said Dr. Nelson A. Wivel, executive secretary of the committee.

In a related development, researchers in Pittsburgh, Pa., this week reported promising laboratory results with a potential gene therapy for gaucher’s disease, a rare but disabling hereditary ailment.

The federal panel’s decision Thursday comes only three years after scientists discovered the genetic defect responsible for cystic fibrosis, an inherited respiratory disease that currently afflicts about 30,000 Americans and kills most of its victims before age 30.

And it was only three months ago that scientists in North Carolina learned how to breed mice that develop cystic fibrosis--a major breakthrough that also will expedite the search for a cure.

Although the experimental gene treatments cannot begin until after final approval is received from the Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health, it is highly unlikely either organization would reject the panel’s decision.

The treatments are tentatively scheduled to start in 1993 with an initial group of 10 patients. The procedure will involve replacing defective cystic fibrosis genes in lung cells with normal genes.

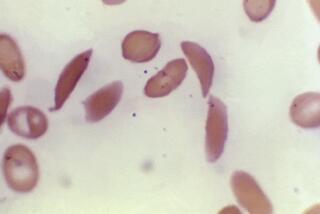

One point of controversy on Thursday was the unusual delivery system for normal genes to replace cystic fibrosis genes: Patients will be given a nasal application of a common cold virus, into which normal genes have been inserted. Researchers expect the virus to spread and invade the lung tissue, with the normal genes replacing the defective ones.

Some panelists expressed concern about possible side effects from the procedure. But the research team, led by Dr. Ronald G. Crystal, chief of the pulmonary branch of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, succeeded in convincing the group that the technique is not likely to cause illness among either patients or health care personnel.

“It’s a low-risk situation, but the benefits are high,” said panelist Roy H. Doi, a biochemistry professor at UC Davis.

Crystal urged families of cystic fibrosis patients not to raise their hopes too high. While the treatments will benefit the patients who receive them, it is not known how long the effects will last.

Gene therapy has two basic approaches. In one, researchers introduce a normal gene into a patient in an attempt to replace a missing gene or to correct a defective one--as in the cystic fibrosis treatments. In the other, scientists design an altered gene that, once introduced into a patient, will assign a cell a new function or enhance an existing function.

The first of the ongoing experimental gene-therapy treatments involved an extremely rare disease called adenosine deaminase deficiency, which afflicts no more than perhaps 20 people at any time worldwide, according to Wivel.